Dr. Michael Osterholm, Director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) and teaching professor in the Division of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health at the University

With more than 40 years of experience in public health, Dr. Osterholm’s presentation, "Emerging Infections in a Modern World: A View From the Front Windshield and Rearview Mirror," took us on a global, historic and present-day look at the prevalence of infectious disease -- H7N9 influenza, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, West Africa Ebola, Zika - and warned us of what the future might hold.

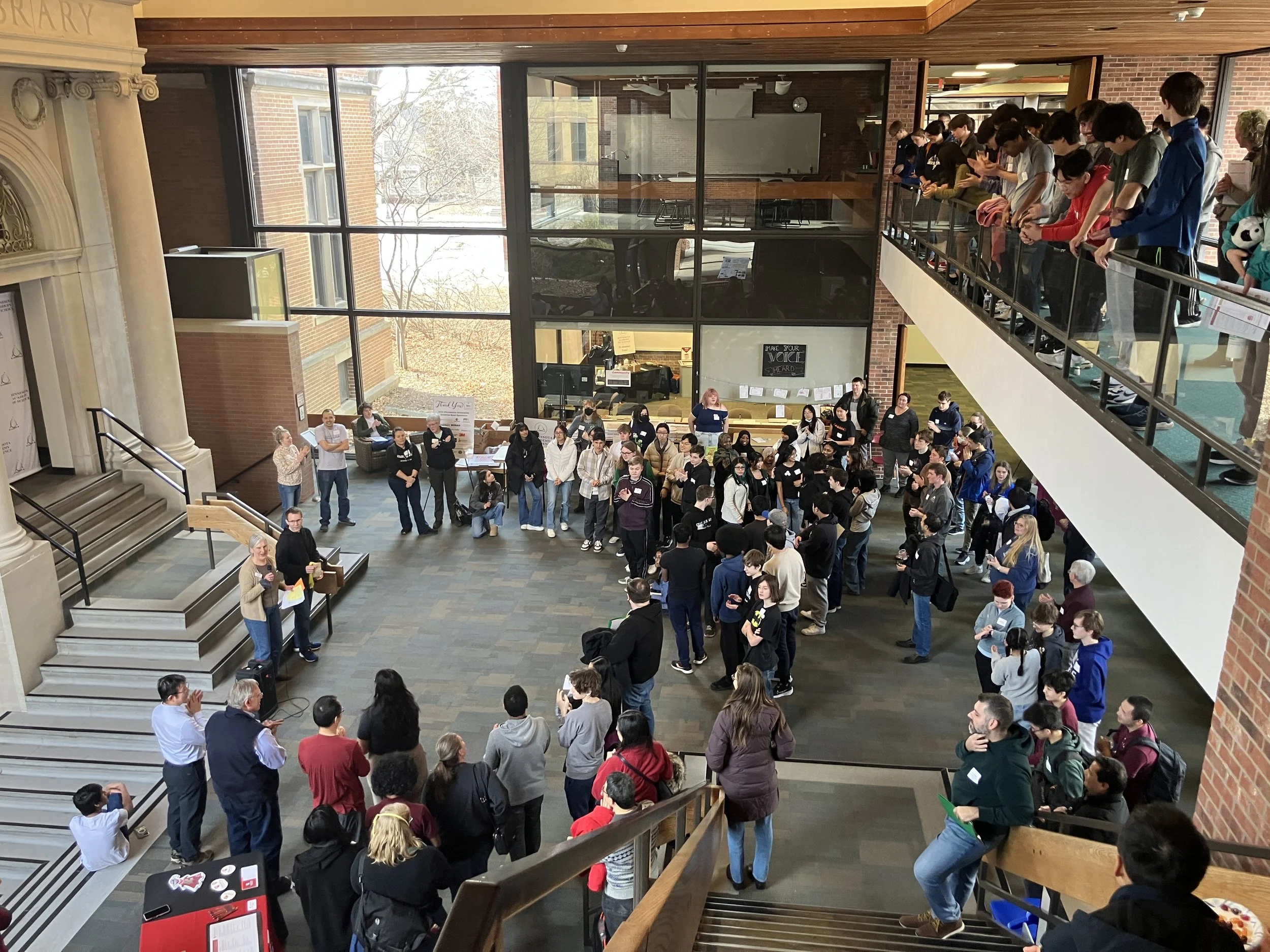

Our more than 60 Minnesota Academy of Science participants in attendance learned not only about the diseases that have the potential to turn into pandemics or major outbreaks, but also about why our world is so much more susceptible to these diseases than we have been in the past.

Dr. Osterholm started off his talk by focusing on what has changed in our world that makes highly infectious diseases so much more worrisome than they have been in our past. Currently our world population is 7.3 billion people, which is double what it was 50 years ago. By 2050 the population is expected to be 11 billion. This burgeoning population has led to large numbers of people living in close quarters, often in unhygienic spaces, in close habitation with animals and insects that are carriers -- breeding grounds for disease.

He said that after he visited Mumbai, India -- where a population larger than Minnesota lives in slums -- it took him weeks to get the unhygienic odor out of his nose.

As the Fragile State Index also reveals, he said, many of the world's countries are not stable -- lacking leadership that would provide structure for addressing a public health outbreak. He quoted former Sen. Joe Lieberman who indicated, in revealing a 100-page report alongside former Homeland Security Secretary Tom Ridge, that a weaponized virus is easier to create now than other weapons of mass destruction.

As our population has grown in tighter spaces, and our vulnerability to bioterrorism, so has our accessibility to global travel. At one point in our history, it took a year to travel around the world, Dr. Osterholm reminded us. Now we can travel around the world in a day. He shared a website that tracks flights around the world in a 24 hour period. This, too, greatly increases the ability for disease to spread quickly and widely. Barriers such as oceans and mountains, and the fact that half of our population no longer lives in remote villages but in urban centers, means that we are no longer able to contain disease in one small area.

"That we are at high risk is widely underestimated," Dr. Osterholm told us. "Our ability to respond is insufficient. That we will experience major social, economic and political disruption is not unlikely."

He said that he warned 16 months earlier what the growing Zika virus in South America could do -- and few paid attention. [Here is a link to Dr. Osterholm's New York Times op-ed in January 2016.] He showed an image of the plastic trash accumulating in city streets, for example, which is a breeding ground for the mosquitoes just as easily as the rubber tires we've shipped around the world for disposal. [Image at left from Rio de Janeiro.]

He noted that Shanghai alone feeds 100 million chickens -- a highly susceptible bird for disease -- and it takes only 35 days to get from hatching to chicken breast on our plate. These global concerns are much greater than they were 50 years ago, he reminded us.

[See the April 2016 issue of The Lancet for its focus on infectious diseases.]

Dr. Osterholm and his colleagues also are concerned with our ability to deal with the outbreaks and pandemics that are bound to come. Some areas of the world have excellent health care available; others have nearly no health care. And even a strong health care facility -- like the prestigious Samsung Medical Center in South Korea -- is not easily protected from outbreak. More than 165 people were exposed to Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome from exposure, largely in its emergency room, in 2015, causing it to close for several weeks. (see graphic below from Wall Street Journal)

Can you imagine the shaken confidence in public health care that would happen if Mayo Clinic had to close down for six weeks, Dr. Osterholm added. Yet how many people fly from all over the country for medical care at Mayo, or John Hopkins, or Mount Sinai.

We focus so much attention on how to protect ourselves from terrorists -- some thinking a refusal of Muslims or refugees is the answer -- when the toxicity danger can be much closer to home, he indicated. We spend billions in air security. Why do we always have to wait for catastrophe to hit before we pay attention to our other vulnerabilities, Dr. Osterholm asked.

The Limitations of Vaccine

The other major concern is that investment in research and development of vaccines is unable to keep up. He said 1 in 5 attempted vaccines for Ebola worked, with an investment of $100 million. Currently, Dr. Osterholm said, we are not anticipating potential threats, we are reacting to outbreaks that are already happening, and we are only concentrating on managing the disease, not necessarily studying how to stop it before it starts. And... we repeat the cycle of lack of political will to make long-term changes.

When something like the Zika Virus shows up, we throw money into R&D for a vaccine, but then the number of cases decline and we say “oh never mind,” he said, and the funding goes to the next perceived threat. For ebola, for example, we quickly turned from a worried country to one that said, "it's behind us, it's gone, let's move on." But just because the number of cases goes down does not mean the threat of outbreak is gone. Money is still needed to develop vaccines and to research the disease. Pharmaceutical companies also will be less inclined to make the investment in future outbreaks with such a weak track record of recouping their losses.

He said that if the Department of Defense told contractors it wanted a new aircraft, "figure out what would be good, then we'll decide if we want to pay for it" -- it would be a terrible business model. Yet that's what we are doing with pharmaceutical companies. And regardless of how we feel about Big Pharm, Dr. Osterholm said, "strategically our defense against infectious disease is as important as any bullet -- and we don't get it."

Dr. Osterholm compared our response to tackling infectious disease to building a 21st century modern house that uses an 8-track system. Our approach is antiquated. So what does he say we need in order to be successful in dealing with these modern diseases?

Firstly, we need to understand these 21st century diseases within the context of the current time -- not 50 years ago. Secondly, we need to be creative and imaginative with our study of these diseases -- provide a regulatory agency, reduce gaps in safety effectiveness, get more direct input from African public health leaders, sharpen our diagnostics so we can segregate those affected more quickly, for example. And thirdly, we need to improve our business model to maintain industry investment after the initial wave of panic subsides -- there needs to be financial incentive to develop vaccines, as well as do research on the diseases themselves.

The solution, he said, cries out for leadership -- not partisan politics.

In wrapping up his presentation, Dr. Osterholm ended with a quote from "A Christmas Carol." - “Are these the shadows of the things that Will Be, or are they shadows of things that May Be, only?” – Ebenezer Scrooge.